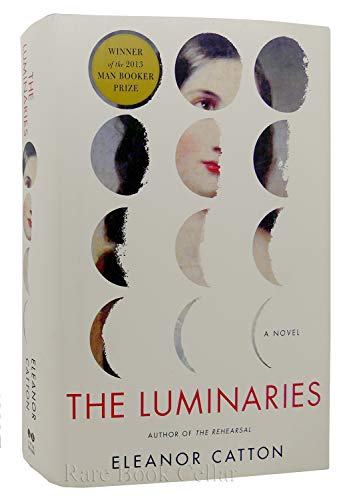

The Luminaries: A Novel (Man Booker Prize) - Hardcover

Synopsis

The bestselling, Man Booker Prize-winning novel hailed as "a true achievement. Catton has built a lively parody of a 19th-century novel, and in so doing created a novel for the 21st, something utterly new. The pages fly."-New York Times Book Review

It is 1866, and Walter Moody has come to stake his claim in New Zealand's booming gold rush. On the stormy night of his arrival, he stumbles across a tense gathering of 12 local men who have met in secret to discuss a series of unexplained events: a wealthy man has vanished, a prostitute has tried to end her life, and an enormous cache of gold has been discovered in the home of a luckless drunk. Moody is soon drawn into a network of fates and fortunes that is as complex and exquisitely ornate as the night sky.

Richly evoking a mid-nineteenth-century world of shipping, banking, and gold rush boom and bust, The Luminaries is at once a fiendishly clever ghost story, a gripping page-turner, and a thrilling novelistic achievement. It richly confirms that Eleanor Catton is one of the brightest stars in the international literary firmament.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

About the Author

Eleanor Catton was awarded the 2013 Man Booker Prize for The Luminaries. Her first novel, The Rehearsal, won the 2009 Betty Trask Award and the Adam Prize in Creative Writing, and was long-listed for the Orange Prize and short-listed for the Dylan Thomas Prize. She holds an MFA from the Iowa Writers' Workshop and an MA in fiction writing from the International Institute of Modern Letters. Born in Canada, Catton was raised in New Zealand, where she now lives.

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.

The Luminaries

A Novel

By Eleanor CattonLittle, Brown and Company

All rights reserved.

CHAPTER 1

A Sphere within a Sphere

27 January 1866

Mercury in Sagittarius

In which a stranger arrives in Hokitika; a secret council is disturbed; WalterMoody conceals his most recent memory; and Thomas Balfour begins to tell astory.

The twelve men congregated in the smoking room of the Crown Hotel gave theimpression of a party accidentally met. From the variety of their comportmentand dress—frock coats, tailcoats, Norfolk jackets with buttons of horn, yellowmoleskin, cambric, and twill—they might have been twelve strangers on a railwaycar, each bound for a separate quarter of a city that possessed fog and tidesenough to divide them; indeed, the studied isolation of each man as he poredover his paper, or leaned forward to tap his ashes into the grate, or placed thesplay of his hand upon the baize to take his shot at billiards, conspired toform the very type of bodily silence that occurs, late in the evening, on apublic railway—deadened here not by the slur and clunk of the coaches, but bythe fat clatter of the rain.

Such was the perception of Mr. Walter Moody, from where he stood in the doorwaywith his hand upon the frame. He was innocent of having disturbed any kind ofprivate conference, for the speakers had ceased when they heard his tread in thepassage; by the time he opened the door, each of the twelve men had resumed hisoccupation (rather haphazardly, on the part of the billiard players, for theyhad forgotten their places) with such a careful show of absorption that no oneeven glanced up when he stepped into the room.

The strictness and uniformity with which the men ignored him might have arousedMr. Moody's interest, had he been himself in body and temperament. As it was, hewas queasy and disturbed. He had known the voyage to West Canterbury would befatal at worst, an endless rolling trough of white water and spume that ended onthe shattered graveyard of the Hokitika bar, but he had not been prepared forthe particular horrors of the journey, of which he was still incapable ofspeaking, even to himself. Moody was by nature impatient of any deficiencies inhis own person—fear and illness both turned him inward—and it was for thisreason that he very uncharacteristically failed to assess the tenor of the roomhe had just entered.

Moody's natural expression was one of readiness and attention. His gray eyeswere large and unblinking, and his supple, boyish mouth was usually poised in anexpression of polite concern. His hair inclined to a tight curl; it had fallenin ringlets to his shoulders in his youth, but now he wore it close against hisskull, parted on the side and combed flat with a sweet-smelling pomade thatdarkened its golden hue to an oily brown. His brow and cheeks were square, hisnose straight, and his complexion smooth. He was not quite eight-and-twenty,still swift and exact in his motions, and possessed of the kind of roguish,unsullied vigor that conveys neither gullibility nor guile. He presented himselfin the manner of a discreet and quick-minded butler, and as a consequence wasoften drawn into the confidence of the least voluble of men, or invited tobroker relations between people he had only lately met. He had, in short, anappearance that betrayed very little about his own character, and an appearancethat others were immediately inclined to trust.

Moody was not unaware of the advantage his inscrutable grace afforded him. Likemost excessively beautiful persons, he had studied his own reflection minutelyand, in a way, knew himself from the outside best; he was always in some chamberof his mind perceiving himself from the exterior. He had passed a great manyhours in the alcove of his private dressing room, where the mirror tripled hisimage into profile, half-profile, and square: Van Dyck's Charles, though a gooddeal more striking. It was a private practice, and one he would likely havedenied—for how roundly self-examination is condemned, by the moral prophets ofour age! As if the self had no relation to the self, and one only looked inmirrors to have one's arrogance confirmed; as if the act of self-regarding wasnot as subtle, fraught and ever-changing as any bond between twin souls. In hisfascination Moody sought less to praise his own beauty than to master it.Certainly whenever he caught his own reflection, in a window box, or in a paneof glass after nightfall, he felt a thrill of satisfaction— but as an engineermight feel, chancing upon a mechanism of his own devising and finding itsplendid, flashing, properly oiled and performing exactly as he had predicted itshould.

He could see his own self now, poised in the doorway of the smoking room, and heknew that the figure he cut was one of perfect composure. He was near tremblingwith fatigue; he was carrying a leaden weight of terror in his gut; he feltshadowed, even dogged; he was filled with dread. He surveyed the room with anair of polite detachment and respect. It had the appearance of a place rebuiltfrom memory after a great passage of time, when much has been forgotten(andirons, drapes, a proper mantel to surround the hearth) but small detailspersist: a picture of the late Prince Consort, for example, cut from a magazineand affixed with shoe tacks to the wall that faced the yard; the seam down themiddle of the billiard table, which had been sawn in two on the Sydney docks tobetter survive the crossing; the stack of old broadsheets upon the secretary,the pages thinned and blurry from the touch of many hands. The view through thetwo small windows that flanked the hearth was over the hotel's rear yard, amarshy allotment littered with crates and rusting drums, separated from theneighboring plots only by patches of scrub and low fern, and, to the north, by arow of laying hutches, the doors of which were chained against thieves. Beyondthis vague periphery, one could see sagging laundry lines running back and forthbehind the houses one block to the east, latticed stacks of raw timber, pigpens,piles of scrap and sheet iron, broken cradles and flumes—everything abandoned,or in some relative state of disrepair. The clock had struck that late hour oftwilight when all colors seem suddenly to lose their richness, and it wasraining hard; through the cockled glass the yard was bleached and fading.Inside, the spirit lamps had not yet succeeded the sea-colored light of thedying day, and seemed by virtue of their paleness to accent the generalcheerlessness of the room's decor.

For a man accustomed to his club in Edinburgh, where all was lit in hues of redand gold, and the studded couches gleamed with a fatness that reflected thegirth of the gentlemen upon them; where, upon entering, one was given a softjacket that smelled pleasantly of anise, or of peppermint, and thereafter themerest twitch of one's finger toward the bell-rope was enough to summon a bottleof claret on a silver tray, the prospect was a crude one. But Moody was not aman for whom offending standards were cause enough to sulk: the rough simplicityof the place only made him draw back internally, as a rich man will step swiftlyto the side, and turn glassy, when confronted with a beggar in the street. Themild look upon his face did not waver as he cast his gaze about, but inwardly,each new detail—the mound of dirty wax beneath this candle, the rime of dustaround that glass—caused him to retreat still further into himself, and steelhis body all the more rigidly against the scene.

This recoil, though unconsciously performed, owed less to the common prejudicesof high fortune—in fact Moody was only modestly rich, and often gave coins topaupers, though (it must be owned) never without a small rush of pleasure forhis own largesse—than to the personal disequilibrium over which the man wascurrently, and invisibly, struggling to prevail. This was a gold town, afterall, new-built between jungle and surf at the southernmost edge of the civilizedworld, and he had not expected luxury.

The truth was that not six hours ago, aboard the barque that had conveyed himfrom Port Chalmers to the wild shard of the Coast, Moody had witnessed an eventso extraordinary and affecting that it called all other realities into doubt.The scene was still with him—as if a door had chinked open, in the corner of hismind, to show a band of graying light, and he could not now wish the darknessback again. It was costing him a great deal of effort to keep that door fromopening further. In this fragile condition, any unorthodoxy or inconvenience waspersonally affronting. He felt as if the whole dismal scene before him was anaggregate echo of the trials he had so lately sustained, and he recoiled from itin order to prevent his own mind from following this connexion, and returning tothe past. Disdain was useful. It gave him a fixed sense of proportion, arightfulness to which he could appeal, and feel secure.

He called the room luckless, and meager, and dreary—and with his inner mind thusfortified against the furnishings, he turned to the twelve inhabitants. Aninverted pantheon, he thought, and again felt a little steadier, for havingindulged the conceit.

The men were bronzed and weathered in the manner of all frontiersmen, their lipschapped white, their carriage expressive of privation and loss. Two of theirnumber were Chinese, dressed identically in cloth shoes and gray cotton shifts;behind them stood a Maori native, his face tattooed in whorls of greenish-blue.Of the others, Moody could not guess the origin. He did not yet understand howthe diggings could age a man in a matter of months; casting his gaze around theroom, he reckoned himself the youngest man in attendance, when in fact severalwere his juniors and his peers. The glow of youth was quite washed from them.They would be crabbed forever, restless, snatching, gray in body, coughing dustinto the brown lines of their palms. Moody thought them coarse, even quaint; hethought them men of little influence; he did not wonder why they were so silent.He wanted a brandy, and a place to sit and close his eyes.

He stood in the doorway a moment after entering, waiting to be received, butwhen nobody made any gesture of welcome or dismissal he took another stepforward and pulled the door softly closed behind him. He made a vague bow in thedirection of the window, and another in the direction of the hearth, to sufficeas a wholesale introduction of himself, then moved to the side table and engagedhimself in mixing a drink from the decanters set out for that purpose. He chosea cigar and cut it; placing it between his teeth, he turned back to the room,and scanned the faces once again. Nobody seemed remotely affected by hispresence. This suited him. He seated himself in the only available armchair, lithis cigar, and settled back with the private sigh of a man who feels his dailycomforts are, for once, very much deserved.

His contentment was short-lived. No sooner had he stretched out his legs andcrossed his ankles (the salt on his trousers had dried, most provokingly, intides of white) than the man on his immediate right leaned forward in his chair,prodded the air with the stump of his own cigar, and said, "Look here—you'vebusiness, here at the Crown?"

This was rather abruptly phrased, but Moody's expression did not register asmuch. He bowed his head politely and explained that he had indeed secured a roomupstairs, having arrived in town that very evening.

"Just off the boat, you mean?"

Moody bowed again and affirmed that this was precisely his meaning. So that theman would not think him short, he added that he was come from Port Chalmers,with the intention of trying his hand at digging for gold.

"That's good," the man said. "That's good. New finds up the beach—she's ripewith it. Black sands: that's the cry you'll be hearing; black sands upCharleston way; that's north of here, of course—Charleston. Though you'll stillmake pay in the gorge. You got a mate, or come over solo?"

"Just me alone," Moody said.

"No affiliations!" the man said.

"Well," Moody said, surprised again at his phrasing, "I intend to make my ownfortune, that's all."

"No affiliations," the man repeated. "And no business; you've no business, hereat the Crown?"

This was impertinent—to demand the same information twice—but the man seemedgenial, even distracted, and he was strumming with his fingers at the lapel ofhis vest. Perhaps, Moody thought, he had simply not been clear enough. He said,"My business at this hotel is only to rest. In the next few days I will makeinquiries around the diggings—which rivers are yielding, which valleys are dry—and acquaint myself with the digger's life, as it were. I intend to stay here atthe Crown for one week, and after that, to make my passage inland."

"You've not dug before, then."

"No, sir."

"Never seen the color?"

"Only at the jeweler's—on a watch, or on a buckle; never pure."

"But you've dreamed it, pure! You've dreamed it—kneeling in the water, siftingthe metal from the grit!"

"I suppose ... well no, I haven't, exactly," Moody said. The expansive style ofthis man's speech was rather peculiar to him: for all the man's apparentdistraction, he spoke eagerly, and with an energy that was almost importunate.Moody looked around, hoping to exchange a sympathetic glance with one of theothers, but he failed to catch anybody's eye. He coughed, adding, "I supposeI've dreamed of what comes afterward—that is, what the gold might lead to, whatit might become."

The man seemed pleased by this answer. "Reverse alchemy, is what I like to callit," he said, "the whole business, I mean—prospecting. Reverse alchemy. Do yousee—the transformation—not into gold, but out of it—"

"It is a fine conceit, sir,"—reflecting only much later that this notion chimedvery nearly with his own recent fancy of a pantheon reversed.

"And your inquiries," the man said, nodding vigorously, "your inquiries—you'llbe asking around, I suppose—what shovels, what cradles—and maps and things."

"Yes, precisely. I mean to do it right."

The man threw himself back into his armchair, evidently very amused. "One week'sboard at the Crown Hotel—just to ask your questions!" He gave a little shout oflaughter. "And then you'll spend two weeks in the mud, to earn it back!"

Moody recrossed his ankles. He was not in the right disposition to return theother man's energy, but he was too rigidly bred to consider being impolite. Hemight have simply apologized for his discomfiture, and admitted some kind ofgeneral malaise—the man seemed sympathetic enough, with his strumming fingers,and his rising gurgle of a laugh—but Moody was not in the habit of speakingcandidly to strangers, and still less of confessing illness to another man. Heshook himself internally and said, in a brighter tone of voice,

"And you, sir? You are well established here, I think?"

"Oh, yes," replied the other. "Balfour Shipping, you'll have seen us, right pastthe stockyards, prime location—Wharf-street, you know. Balfour, that's me.Thomas is my Christian name. You'll need one of those on the diggings: no mangoes by Mister in the gorge."

"Then I must practice using mine," Moody said. "It is Walter. Walter Moody."

"Yes, and they'll call you anything but Walter too," Balfour said, striking hisknee. "'Scottish Walt,' maybe. 'Two-Hand Walt,' maybe. 'Wally Nugget.' Ha!"

"That name I shall have to earn."

Balfour laughed. "No earning about it," he said. "Big as a lady's pistol, someof the ones I've seen. Big as a lady's—but, I'm telling you, not half as hard toput your hands on."

Thomas Balfour was around fifty in age, compact and robust in body. His hair wasquite gray, combed backward from his forehead, and long about the ears. He worea spade-beard, and was given to stroking it downward with the cup of his handwhen he was amused—he did this now, in pleasure at his own joke. His prosperitysat easily with him, Moody thought, recognizing in the man that relaxed sense ofentitlement that comes when a lifelong optimism has been ratified by success. Hewas in shirtsleeves; his cravat, though of silk, and finely wrought, was spottedwith gravy and coming loose at the neck. Moody placed him as a libertarian—harmless, renegade in spirit, and cheerful in his effusions.

"I am in your debt, sir," he said. "This is the first of many customs of which Iwill be entirely ignorant, I am sure. I would have certainly made the error ofusing a surname in the gorge."

(Continues...)

Excerpted from The Luminaries by Eleanor Catton. Copyright © 2013 Eleanor Catton. Excerpted by permission of Little, Brown and Company.

All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Excerpts are provided by Dial-A-Book Inc. solely for the personal use of visitors to this web site.

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

US$ 20.00 shipping from U.S.A. to Hong Kong

Destination, rates & speedsBuy New

View this itemUS$ 30.00 shipping from U.S.A. to Hong Kong

Destination, rates & speedsSearch results for The Luminaries: A Novel (Man Booker Prize)

The Luminaries : A Novel

Seller: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, U.S.A.

Condition: Very Good. First Edition. Used book that is in excellent condition. May show signs of wear or have minor defects. Seller Inventory # 4107938-75

Quantity: 2 available

The Luminaries : A Novel

Seller: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, U.S.A.

Condition: Good. First Edition. Used book that is in clean, average condition without any missing pages. Seller Inventory # 3947328-75

Quantity: 8 available

The Luminaries : A Novel

Seller: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, U.S.A.

Condition: Good. First Edition. Former library book; may include library markings. Used book that is in clean, average condition without any missing pages. Seller Inventory # GRP92078572

Quantity: 10 available

The Luminaries : A Novel

Seller: Better World Books: West, Reno, NV, U.S.A.

Condition: Good. First Edition. Used book that is in clean, average condition without any missing pages. Seller Inventory # 3947328-75

Quantity: 3 available

The Luminaries : A Novel

Seller: Better World Books: West, Reno, NV, U.S.A.

Condition: Good. First Edition. Former library book; may include library markings. Used book that is in clean, average condition without any missing pages. Seller Inventory # GRP92078572

Quantity: 4 available

The Luminaries : A Novel

Seller: Better World Books: West, Reno, NV, U.S.A.

Condition: Very Good. First Edition. Used book that is in excellent condition. May show signs of wear or have minor defects. Seller Inventory # 4107938-75

Quantity: 1 available

The Luminaries : A Novel

Seller: Better World Books: West, Reno, NV, U.S.A.

Condition: Very Good. First Edition. Former library book; may include library markings. Used book that is in excellent condition. May show signs of wear or have minor defects. Seller Inventory # GRP83175395

Quantity: 2 available

The Luminaries: A Novel (Man Booker Prize)

Seller: Wonder Book, Frederick, MD, U.S.A.

Condition: Very Good. Very Good condition. Very Good dust jacket. A copy that may have a few cosmetic defects. May also contain light spine creasing or a few markings such as an owner's name, short gifter's inscription or light stamp. Seller Inventory # B05N-00327

Quantity: 1 available

The Luminaries: A Novel

Seller: medimops, Berlin, Germany

Condition: very good. Gut/Very good: Buch bzw. Schutzumschlag mit wenigen Gebrauchsspuren an Einband, Schutzumschlag oder Seiten. / Describes a book or dust jacket that does show some signs of wear on either the binding, dust jacket or pages. Seller Inventory # M00316074314-V

Quantity: 1 available

The Luminaries (Man Booker Prize for Fiction)

Seller: Greener Books, London, United Kingdom

Hardcover. Condition: Used; Very Good. **SHIPPED FROM UK** We believe you will be completely satisfied with our quick and reliable service. All orders are dispatched as swiftly as possible! Buy with confidence! Greener Books. Seller Inventory # 4566279

Quantity: 1 available